Maintaining Fitness During the Offseason: Tips for Enjoying Downtime

The off-season is a period of rest and recovery after a major event or the end of the racing season, during which athletes can mentally and physically freshen up while minimising loss of training adaptations.

Many athletes struggle with the period after a major event, or the final race of the season – known as the off-season. You’ve been so focused on your training for and nailing your event, and likely gotten into a routine of balancing your training programme around work and family. After the event, motivation can dwindle, and it can be tricky to figure out what it is you are trying to do with your training, and even if you should be training at all!

The purpose of the off-season, which is essential, is to physically and mentally freshen up whilst minimising the loss of those hard-earned adaptations you accrued in the build-up to the previous event. You can’t always just keep training; it is necessary to pull back, let any niggles clear, and reconnect with the other aspects of your life that training has dominated! Not taking an off-season leaves you at risk of physically or mentally burning out in the next programme.

Detraining: What happens when we stop training?

If we stop training, we start to lose some of the hard-earned adaptations we had gained through training, with obvious effects on performance. The loss of adaptations when we stop training is called detraining, and detraining can be considered in terms of its short (<4 weeks of rest) and long (>4 weeks of rest) effects.

The detraining-induced loss of training adaptations was brilliantly reviewed by Iñigo Mujika and Sabino Padillo back in 2000 (1, 2). They described how, with short-term detraining, we experience a relatively rapid loss of aerobic capacity (V̇O2max), likely resulting from reduced blood volume. From a metabolic standpoint, we can expect reduced fat and increased carbohydrate oxidation at given speeds and power outputs, as well as lowered muscle glycogen stores and lactate thresholds. This all simply reflects lost fitness. Unsurprisingly, our endurance performance goes down, too.

These effects are exacerbated when detraining is extended for longer than four weeks. As endurance athletes, we may also reduce our slow-twitch fibre proportion, which is unhelpful considering we want those fatigue-resistant, type I fibres for long-duration events like triathlons. These detraining-induced changes, which have all been shown in the literature, are perhaps not surprising; we all know we lose fitness when we stop training.

It’s not all doom and gloom: What training should we do in the off-season?

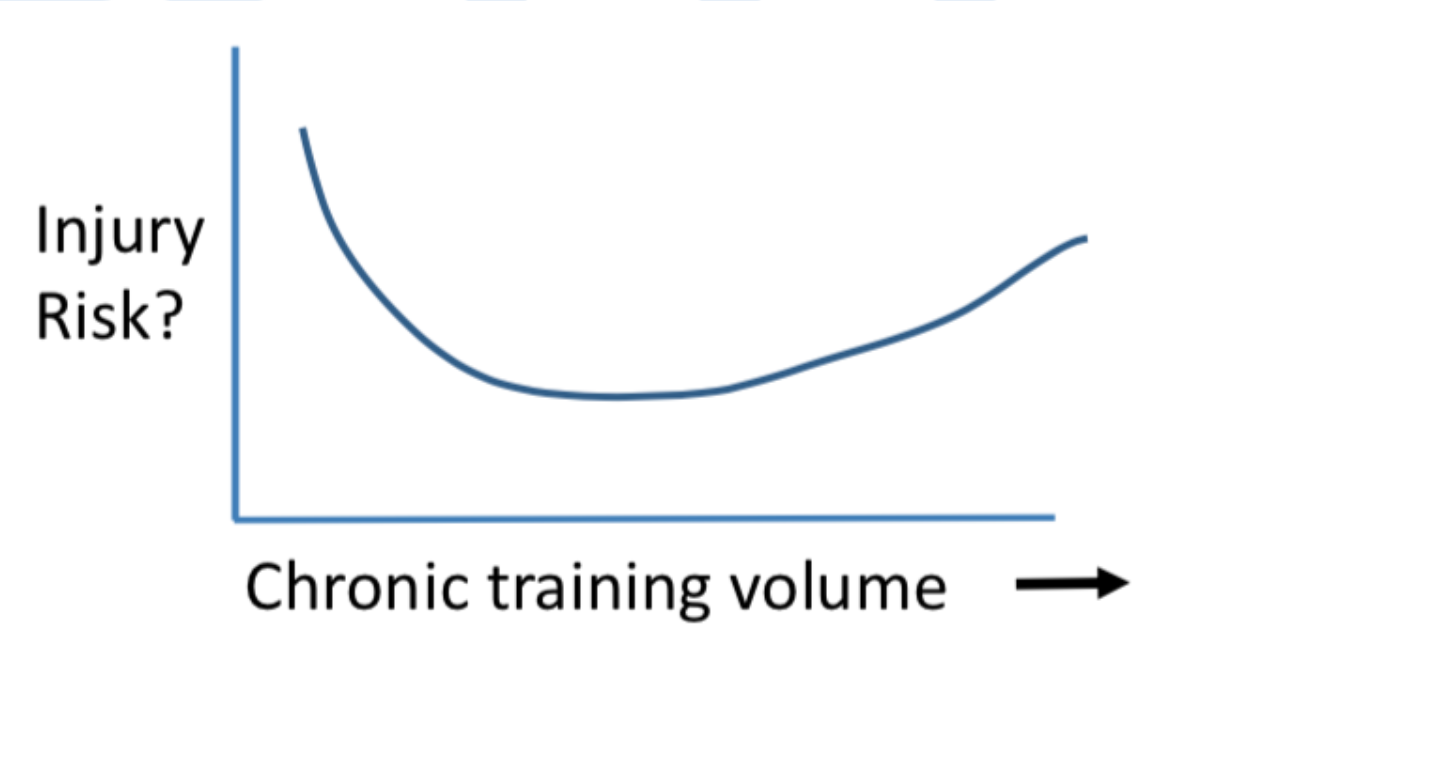

I have not written the above to try and scare you into training as hard as ever during your off-season. As I said, having downtime after a big event is important; we all need time to mentally and physically refresh and reconnect with aspects of our lives (family for many of us) that training may have dominated. We must also allow niggles we’ve picked up in training and racing to subside. What I am trying to do here is show why including a ‘maintenance stimulus’, or a little training to keep you ticking over, is useful in the initial part of your off-season; the purpose of the maintenance stimulus is to hold on to as many of those adaptations as possible, whilst giving you the refresh you need after the build-up for an event. This mindset is similar to what use when designing a taper when training is designed to dissipate fatigue and maximise the retention of adaptations before an event (3). Furthermore, doing some training reduces the risk of injury when you return to training. It’s well established in the literature that the greatest risk of injury is at the start of training after a resting period and under very high training loads (see Figure 1). Personally, as I’ve got older, taking 3-4 weeks of no training at all at the end of the racing season is a recipe for disaster. Indeed, research has shown an increased injury risk in amateur triathletes training <8 or >15 hours.week-1 over a three-year period (5).

So, in practical terms, what should we do to achieve this? Our overall training volume will need to go down, or it’s not an off-season. My advice is to start your off-season by reducing your training frequency substantially; that is, the number of sessions you do each week. Reduce the duration of the sessions that you do, too, particularly the midweek sessions that are often harder to squeeze in around work and family commitments.

We typically think of off-season training in terms of emphasising what training you do on low-intensity work, which is quite right and a valuable opportunity to work on your so-called aerobic base before launching back into training again. Therefore, I recommend keeping almost everything you do below that first threshold in the moderate domain. That should keep the stress associated with the sessions low but keep stimulating those slow-twitch fibres that are so key in endurance sports. With the athletes I coach, I encourage them to hang up the road bike and ride their Mountain Bike a lot more if they have one. I personally love doing this as well.

Focusing on technique-based sessions in swimming is also a great way to stimulate your aerobic base and hone your technique. We all know this is a critical component of fast swimming, and the off-season is a great time to work on this.

That said, some evidence is that including a small dose of high-intensity interval training in your off-season is worth thinking about – perhaps once per week or so. A great study to support this was published in 2014 by Bent Rønnestad and colleagues in Norway (4). In that study, well-trained cyclists did either one high-intensity interval training session per week or none during an eight-week off-season. Those who did the intervals during the off-season better hold on to things like their V̇O2max and, crucially, seemed to be in better shape even after the first training block following the off-season. Therefore, adding a small amount of high-intensity work during the off-season helped the cyclists hold on to adaptations gained throughout the previous season, and provided them with a better springboard to launch into that first training block. Therefore, I like to keep a little high-intensity work in my off-season.

Something else that needs to be utilised during this period is resistance training. As endurance athletes, we know the benefits that doing some resistance training can have – improved tissue resilience, movement economy, and lowered risk of injury, to name a few – but often struggle to get as much in as we’d like during the season. This is particularly the case for us as long-distance triathletes must train in all three disciplines. Therefore, when training volume is low, I think the off-season is a great chance to get a solid dose of resistance training in, to put us in great shape, ready to hit the ground running in the first block of the season.

Example off-season week vs in-season week

Below (Figure 2) is a 1-week example where we have a typical off-season training week (above) contrasted with a typical in-season week (below). Notice the lowered training frequency and overall volume in the off-season, albeit with a high-intensity interval training session, a longer (ish) ride, and two resistance training sessions.

Summary

The off-season is always a tricky period to manage. I hope in this blog I’ve provided some key tips to help you plan your next break:

- Reduce overall training volume by reducing training frequency, particularly midweek

- Consider including a weekly high-intensity interval training session to maintain adaptations, with everything else of low intensity.

- Get plenty of strength and mobility training to prepare your body for the next training cycle.

- Spend time with your family and friends

References

- Mujika I, Padilla S. Detraining: Loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Part I: Short term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med 30: 79–87, 2000.

- Mujika I, Padilla S. Detraining: Loss of training induced physiological and performance adaptation. Part II: Long term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med 30: 79–87, 2000. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200030020-00002.

- Mujika I, Padilla S. Scientific bases for precompetition tapering strategies. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35: 1182–1187, 2003. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074448.73931.11.

- Rønnestad BR, Askestad A, Hansen J. HIT maintains performance during the transition period and improves next season performance in well-trained cyclists. Eur J Appl Physiol 114: 1831–1839, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00421-014-2919-5.

- Shaw T, Howat P, Trainor M, Maycock B. Training patterns and sports injuries in triathletes. J Sci Med Sport 7: 446–450, 2004.

Comments ()